As retro-gamer gamers, we often scoff at the idea the idea that a game “has aged poorly”. One typical response is to point out how many modern games ‘coddle the player’, and ‘hold their hand’ through every tiny challenge, free of any repercussion from failure. In short, we retro-gamers from upon our highest of horses decree, “The game has aged perfectly fine, you just can’t see past all the myriad ways that modern gaming has pampered you.” This is problematic for (at least) two reasons. First and foremost is the way that this idea drifts somewhere within the sphere of ageisim. The idea that older games are granted ‘unassailable’ status simply by virtue of age, whereas newer games somehow warrant increased scrutiny by that same virtue is silly. Secondly, the idea of “inherent retro-game superiority” becomes dubious, because, well … some games really have aged poorly. And that pill can be doubly-tough to swallow when said game is considered to be something of a classic within the retro-gaming community. So, um yeeeah … with all that in mind let’s dive into this review of Phantasy Star II!

Now before the torches and pitchforks come out, let me make clear that Phantasy Star II absolutely contains some elements which have stood the test of time. First of all … just get a load of that title screen! It’s easily one of the most beautiful and iconic title screens to have emerged from the 16-bit era. Admittedly, when the first nice thing I can say about Phantasy Star II is that “it has a pretty title screen”, that may not bode well for the remainder of the game. Or perhaps it’s simply the first impressive element one notices when loading it up. To put your mind at ease, Phantasy Star II does indeed contain levels of quality beyond that seen on the title screen. But before we hit the start button and move past that gorgeous title screen, let’s discuss some historical perspective, as I think that best sets the stage for the remainder of the review.

The original Phantasy Star is often well regarded as a classic Sega Master System title. Personally I’d even call it the best JRPG for the SMS. At the time of release, Phantasy Star was remarkably innovative in a number of ways. Rather than focusing on standard sword & sorcery fare, Phantasy Star was set within the framework of a classic space opera. This allowed for unique worldbuilding elements and storytelling not possible within the realms of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest and the like. As opposed to the static unchanging overhead perspective featured in those other games, all the ‘dungeons’ in Phantasy Star switched to a first-person dungeon-crawling perspective. The way the game shifted perspectives between environments was another prominent feature that made Phantasy Star stand out as unique among its contemporaries. Admittedly the combat mechanics in Phantasy Star were similar to those found in Dragon Quest, but set against a backdrop of these other unique elements it didn’t necessarily feel derivative. All told, Phantasy Star was quite an innovative JRPG and can rightly be hailed as a groundbreaking title for the SMS.

So in 1989, the expectations for Phantasy Star II were understandably high. This was one of the earliest JRPGs released for Genesis, and as the sequel to the premiere JRPG on SMS, fans were eager to see what innovations Phantasy Star II had in store for the dawn of the 16-bit era. And by some measures it did push the genre forward in interesting ways. Narratively Phantasy Star II was very solid, and dare I say, even ahead of its time (more on that in a sec). But in terms of mechanics and gameplay, it’s almost like Phantasy Star II was still mired in 8-bit RPG conventions. Charitably, it needs to be said that in 1989, the prevailing philosophy of most game design was still firmly rooted in an 8-bit approach. Sure 16-bit systems were the hot new commodity in Japan, but developers were still figuring out how to make 16-bit systems truly sing. So the fact that Phantasy Star II feels like a slightly up-resed 8-bit title is understandable. But in other ways, Phantasy Star II was a regression even with regard to the 8-bit game that preceded it. Gone were the first-person dungeons that had been such a distinguishing feature of the first title. And despite it having made the technological leap to a 16-bit system, other 8-bit JRPG titles were continuing to push the genre forward into unexplored territory. Games like Mother (1989) and Sweet Home (1989) had expanded on narrative possibilities within the genre, whereas Final Fantasy had practically revolutionized how JRPG games would operate mechanically well into the next decade. Meanwhile Dragon Quest III (1988) had neatly achieved basically all of the above, and a full year earlier than the rest. So it’s not like Phantasy Star II was a bad game by any means, but it did feel like a bit of a regression both in comparison to its direct predecessor, and within the gaming industry at large.

We’ll talk about some of those regressive features in a minute, but first I’d like to touch on the story elements being as this is one area in which Phantasy Star II elevated itself as forward thinking and ahead of the curve in terms of sophistication. As in the first game, the story unfolds across the Algol solar system, although 1000 years have passed since the events of Phantasy Star. Accordingly, much has changed throughout the Algol System. The system itself is now referred to as Algo. Mota where much of this game takes place was known as ‘Motavia’ in the original game. In the intervening centuries, Mota has been terraformed from a barren dessert planet (as seen in the original title) into a lush and fertile paradise, thanks to the mechanizations of an omnipotent super-computer called … Mother Brain (hey, I’m sure it’s a very common name in other galaxies). Mother Brain has basically ‘freed’ the people of Mota from all toil, labor … oh and probably their fundamental autonomy as well. Being as there’s no longer a compelling need to ponder life’s mysteries, the people of Mota have also conveniently forgotten almost all knowledge they might have had regarding their God-computer, other than trusting in Mother Brain to meet their every need. Shockingly that turns out to be a bit of a problem as Mother Brain has gone off the rails just a bit, and is now churning out aggressive mutant lifeforms at an alarming rate. Thus begins our story of Rolf, the government agent assigned to investigate just what the heck is going on with Mother Brain.

Already in the story, we can see emerging themes of over-reliance upon technology and AI. I don’t know about you, but I’m filled with relief that those concerns have stayed firmly within the realms of science fiction! I’m only joking of course. Science Fiction has always provided a roundabout forecast of the future; it’s just a matter of which of its fiction elements become science fact. Obviously the idea that our own technology may eventually exceed our abilities to effectively use and/or understand it has always been an important concept in science fiction. But the fact that we’re talking about these fundamental concepts of science fiction as they apply to a video game released in 1989 is impressive. Phantasy Star II was operating on a level of intellectual depth far beyond, “uh oh, the princess is being held captive by a dragon; better go rescue her!” So that’s one of the ways in which this game was operating on a level of narrative sophistication. It also shows a surprising awareness of where games were headed tonally. Starting in the mid-late 90’s we would increasingly see storytelling mechanisms that relied on ‘grimdark’ elements. Sure it’s become a bit cliché these days, but ‘grimdark’ was the modus operandi of many popular stories during the latter half of the 90’s including movies, comics, and (especially) gaming. But for the most part, we weren’t quite there yet in 1989. Obviously there were some forecasters – selected comics of Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, and Frank Miller all spring immediately to mind of course, and 2000 A.D. (i.e. Judge Dredd) comics had been featuring this type of story for over a decade. But these examples were the early vanguard of this style rather than being representative of any cultural standard (yet). But with all that being said, I would also include Phantasy Star II as part of that vanguard, particularly within realm of gaming. This game had it’s finger on the pulse of where popular video game story conventions were headed over the next decade.

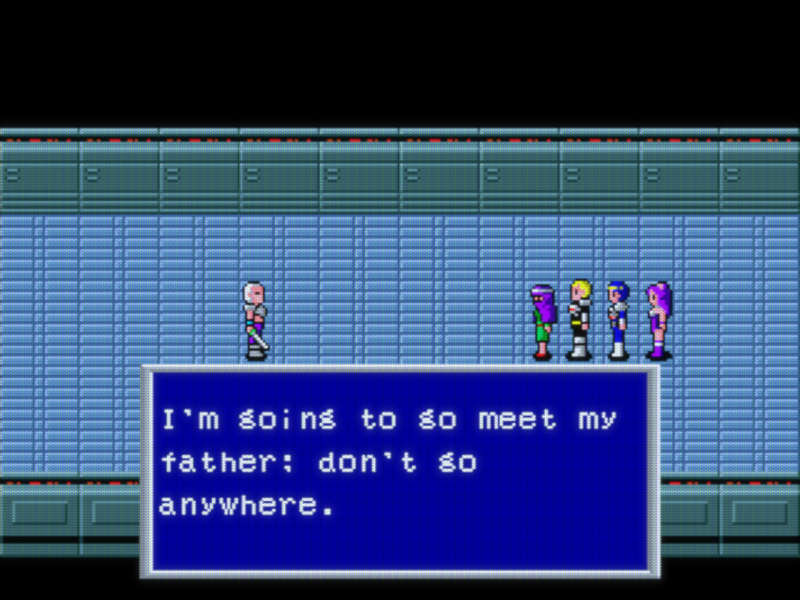

So when you see Phantasy Star II appearing in lists of the best games of all time, it’s most often the story elements that are hailed as being exemplary. Because for better or worse, the actual gaming experience to be had in Phantasy Star II can be a bit uneven at best. So getting back to our game in progress; once we’re able to tear our gaze away from that title screen, we hit start and reach a fairly standard name entry screen in which you’re able to re-name the protagonist as something other than Rolf (should you desire) … except you find that you’re limited to four characters, and they’re all upper case. And look I get it; this was pretty standard in 8-bit games. But for a 16-bit game? I dunno, it feels hinky. Maybe concessions in memory management were necessary to work with other parts of the game. No big deal, character space limitations aren’t even close to being a game killer, so you start getting into the real meat of the game. And as soon as you step out of the front door, you discover that your walking speed is dreadfully slow. It doesn’t really set in just how slow until you factor in two other considerations. The first is that this game is incredibly grindy, potentially moreso than any other retro JRPG I’ve played. So you’re going to need to do a lot of walking around and fighting aimlessly simply to be prepared for the many challenges ahead. If you don’t spend considerable time leveling up, you’re basically already cooked. So when you discover that the random encounter rate is tuned up pretty high, it might initially feel like a boon. Frequent encounters mean more experience gained in a shorter amount of time. And that feels workable until you reach the first of the game’s incredibly labyrinthine dungeons. It’s here you realize that having to fight an encounter every few steps, with limited capacity for healing, and an incredibly slow walking speed might turn out to be more of a hinderance than you realized. This will immediately lead to a realization that you need to level up even more than anticipated … in a continual battle against that slow walking speed and high thresholds for leveling up. I hate to say it, but taken on its own, this can quickly become a formula for mind-numbing boredom.

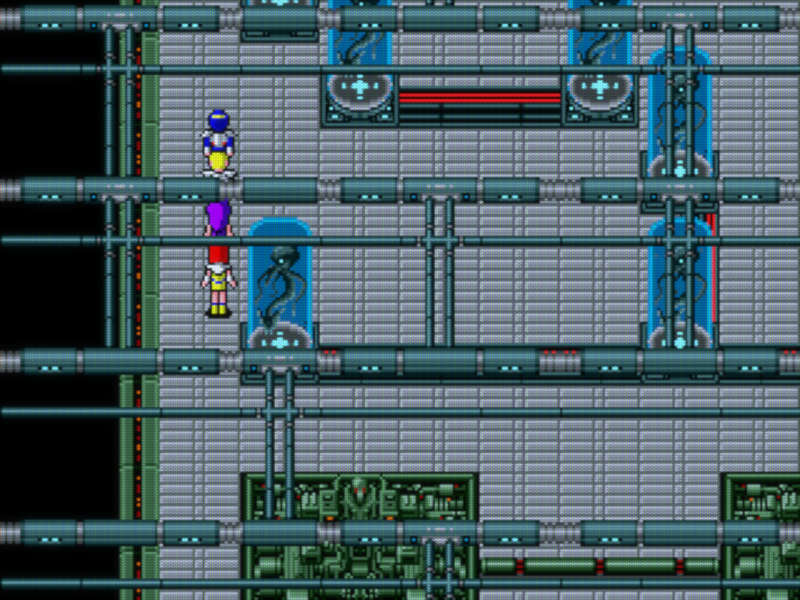

The graphics are nice though, and while in retrospect they don’t quite feel representative of full 16-bit quality, they’re clearly a step up from 8-bit graphics. In one prominent example, the dungeons even feature parallax scrolling of overhead elements, which is to say … a lot of parallax scrolling … to the point that it starts to become a detriment to gameplay, actually. Almost every dungeon in the game features some kind of overhead parallax element, most commonly in the form of snaking pipes or fog effects. The first time you see it, you might nod appreciatively, acknowledging the 16-bit graphical advancements that allowed for the extensive use of this singular effect. But by the time you reach the sixth dungeon where parallax objects are once again obscuring the actual playable map, your wonderment may diminish a bit. By the end of the game, you’re just looking forward to playing a game that doesn’t overuse this one effect at every available opportunity. It’s as if at some stage of development, the designers of Phantasy Star II absolutely fell in love with parallax scrolling and decided to use it as much as they possibly could, ad nauseum.

Combat is also interesting, but not necessarily captivating. It defaults to auto-combat, unless you stop the action and assign your party members different tasks. Then, upon resuming combat, the party will continue to perform those assigned tasks every round until you stop the action again. In a game as grindy as this, the auto-combat is actually a bit of a relief, but … defaulting to auto-combat here almost feels like an explicit admission that the combat is not especially compelling to begin with. And unfortunately, that is often the case outside of a couple of noteworthy boss fights.

As with nearly every RPG I review, I’ve gone on and on for over 2000 words and there are still some elements I’ve neglected to talk about. The cast of party members in Phantasy Star II is varied and interesting which in turn contributes to the overall worldbuilding. One character even has a special ability where she can (randomly) steal from the shops you visit. I thought that was a pretty neat mechanic and I’d love to see it expanded upon in other games. But at the end of the day, what we’re left with is a bit of a mixed bag. Phantasy Star II was an important game, but that doesn’t mean it’s a great gaming experience … particularly under the harsh light of hindsight. It’s certainly worthwhile for JRPG historians, or those especially interested in early sci-fi RPGs. For all others though, I’d point them towards other exemplary RPGs from this era.

Final Verdict: 6 Mothers out of 10 Brains

Leave a Reply